Introduction

We all lead highly unique, extraordinary lives. One might ponder though - upon leaving this earth, what is the legacy we leave behind? More importantly, what kind of impact do we leave? It's intriguing that our stories as leaders, healers, hunters and enthusiasts can be summed through mere carbon atoms that remain on this earth in place of us. Things we did, how long ago we did it and what tools we used might have impacted the world more than we originally thought. This article will take you through the use of carbon dating and its significance in unveiling history.

Understanding carbon-14 dating

Radiocarbon dating, a revolutionary discovery by Willard Libby in 1946, significantly transformed our understanding of the past. Libby, who had built his theories based on Martin Kamen's discovery of the carbon-14 isotope, harnessed this isotope and its radioactive decay for age determination.1

This technique relied on the stable decay of carbon-14 within a sample in order to estimate its age. Thanks to this, science has since made significant advancements in fields like geography, geophysics and more often, in archaeology.2 Although carbon dating is most typically used in determining the age of a biological product for up to about 50,000 years, this is only with traditional methods. Modern-day techniques can go even further for specific materials.3 Libby's discovery meant that any previously living things like bones, people, plants and their creations like paper, weapons, leather and hides could be assigned an age and hence given their own story and significance in their respective periods of history.

One such example was the discovery of Ötzi the Iceman, a well-preserved mummy in the Tyrolean Alps. With the help of carbon-14 dating, scientists were successfully able to place Ötzi as belonging to the Copper Age, and thanks to additional dating of his possessions we were able to understand more about the lifestyle at that time. One such conclusion that scientists were able to make based on Ötzi’s intricate gear and weapons was that he was of high status during his life.4 In addition, his axe, amongst his vast weaponry collection, gave scientists a fresh understanding of the kinds of craftsmanship in the Neolithic period which had not previously been discovered.5 This even allowed us to make connections between Ötzi's axe and different weapons estimated to be of the same age. It permitted us to draw connections between specific artefacts and technological advancements for a particular time period. These discoveries, made possible by carbon dating, went on to significantly enhance our understanding of the Copper Age.

This story goes beyond our infamous mummy; carbon-14 dating can also be used to verify the authenticity of samples. One such popular example was the Lascaux Cave paintings.6 The discovery of the Lascaux paintings and subsequent authentication was a stepping stone in history when it came to understanding the first sign and development of human consciousness.7 The painting went on to further raise questions regarding its symbolism, possible ritualistic meaning, and understanding human behaviour in the Ice Age period.8

What Is life? Spoiler: it’s carbon-14

Carbon is essential for all life on earth. It is required to form complex molecules like proteins, DNA, lipids and, more importantly, sources of universal energy known as carbohydrates.9 Carbohydrates are created by an overall reaction known as photosynthesis, which plants actively carry out in a series of reactions known as the Light Reactions and the Calvin Cycle.10 In summary, plants take up carbon dioxide and water to create carbohydrates for sustenance by plants, grazing animals and humans who ultimately consume both. This can be represented by the following equation:

6CO2 + 6H2O → C6H12O6 + 6O2

We call this movement of carbohydrates through different organisms a food chain.11 These carbohydrates then go on to do their respective biological processes within our body, and as such, we unknowingly have carbon-14 in us. Let’s look at this in smaller steps.

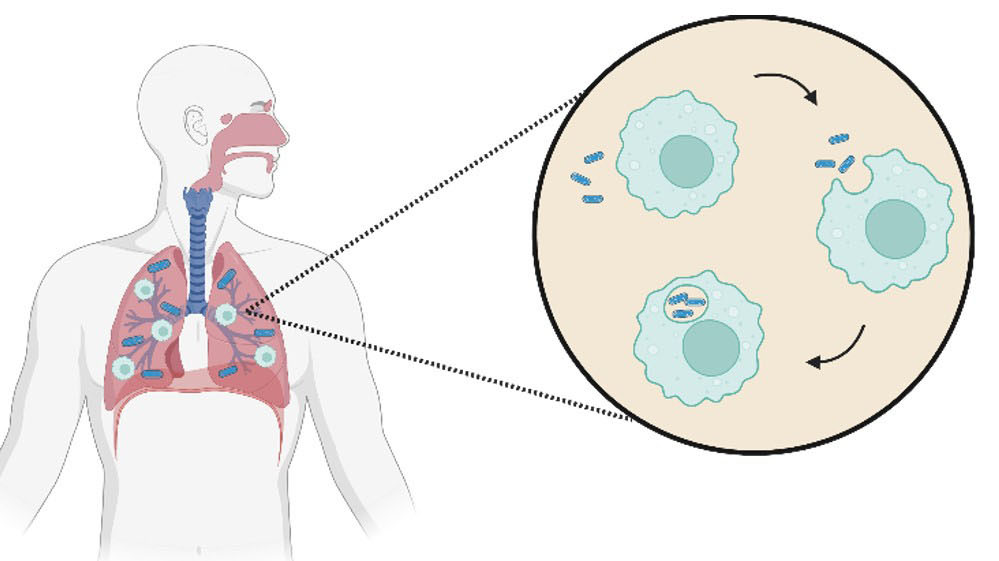

Carbon-14 is a naturally occurring isotope formed in the atmosphere when energetic particles from outer space, known as cosmic rays, interact with nitrogen.11 The nitrogen atom undergoes a series of rapid nuclear reactions to produce carbon-14. Carbon-14 is then oxidised in the atmosphere to form carbon monoxide, a poisonous gas. Luckily, carbon monoxide is only an intermediary, with the resultant product being the creation of carbon dioxide.12 This is the very same carbon dioxide plants use for photosynthesis and, ultimately, humans and animals indirectly take up via the food chain.13 Over time, isotopes, due to the instability caused by the uneven number of neutrons and protons, undergo radioactive decay. This is done to produce a more stable version of the atom.14

The half-life determines the amount and time at which the isotope decays. Half-life is the time it takes one-half of the amount of radioactive isotope to decay.15 Carbon-14 has a half-life of 5,700 years,16 meaning if the sample is present with only half the amount of original carbon-14 atoms, we can safely assume the sample is a whopping 5,700 years old. How exactly does that work? When a living organism dies, it no longer takes up carbon-14, which means the atoms already present within a sample start to undergo beta decay. Beta decay is one of three kinds of nuclear disintegrations, which is responsible for converting one neutron within the nucleus into a proton.17 The resulting product consists of a nitrogen-14 atom with an electron and a burst of energy as a byproduct18 and can be represented by the following equation:

¹⁴C → ¹⁴N + β⁻ + νₑ

To determine how long ago something died, we can consider the ratios of nitrogen-14 atoms to carbon-14 present. We generally see a predictable increase in nitrogen atoms and a steady decrease in carbon-14. The greater the amount of nitrogen-14 present, the more likely the death wasn’t very recent.

Methods of carbon-14 dating

While the sample preparation process for carbon dating remains consistent, the actual measurement of carbon-14 (14C) isotopes can be achieved through three distinct techniques: liquid scintillation counting (LSC), gas proportional counting and accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS). Each method offers unique advantages and considerations.

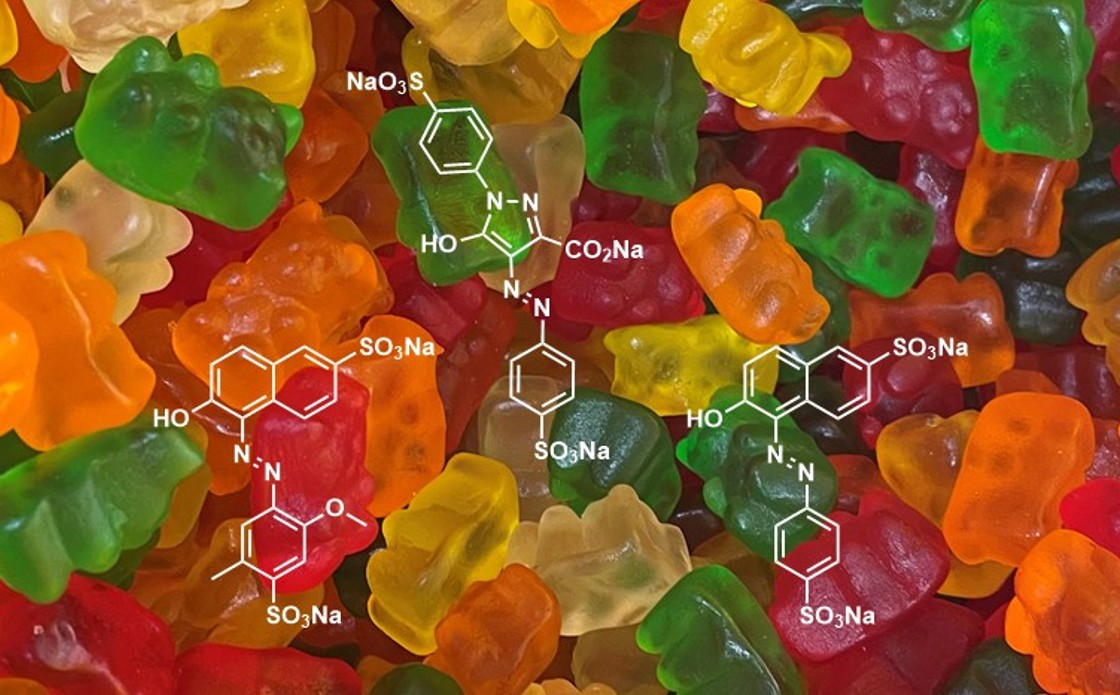

For instance, true to its name, liquid scintillation involves an extracted sample made into a liquid medium through various processes, where it is then observed for decay through a liquid scintillator.19 Liquid scintillation is unique; the sample interacts with apparatus media like 2,5-diphenyloxazole, which are used to extend non-visible wavelengths produced by beta particle interactions with the solvent. As a result, these interactions are seen and recorded as visible flashes.20 Although liquid scintillation is common and widely accessible, its accuracy and efficiency due to its limitations caused by the use of media have raised questions in the past.21

While liquid scintillation involves chemical changes, gas proportional counting is the conversion of the desired sample into a gas. This is a purely physical process. A sample is converted into carbon dioxide, and its decay is then observed in gas-proportional counters.22 This method of dating has a higher rate of efficiency than the former. However, some limitation concerns include the difficulty in converting samples from one state of matter to another.23

Finally, accelerated mass spectrometry is said to be the most effective and modern radiocarbon dating method. First developed in 1970, it is typically preferred over traditional methods like liquid scintillation due to the faster and more sensitive measurements it can perform.24 Unlike other methods that depend on the decay counts, AMS directly calculates the amount of carbon-14 isotopes present within a given sample.25 Additionally, one of the more significant benefits of AMS is the broader range of fields it can be applied to, such as isotope studies for atmospheric and oceanic circulation and isotope-based authentication for minerals, plants and cultural artefacts.26 While being highly efficient in producing more accurate results than its counterparts, AMS is quite costly, and samples are easily contaminated. Hence this technique requires rigorous preparation, which can often be problematic.26

Sample preparation in carbon-14 dating

Carbon dating laboratories receive a wide range of samples in considerable amounts for analysis, including bones, plants and seashells, among others.26 However, not all parts of the sample are suitable for dating, and only the viable fractions that were once a living part of the specimen are closely inspected and isolated as part of the pretreatment process.26 This involves the extraction of collagen from bones and cellulose from plants since they were all living components of the sample. Therefore, in the case of rocks and certain metals, direct dating is not possible due to the lack of carbon. Instead, organic samples like wood or charcoal, which can be found embedded within the rock, are extracted.26 During the pretreatment process, especially for bones, the sample is inspected and crushed using a mortar and pestle to increase the surface area where the reaction can occur. This is done to speed up the reaction rate and produce the desired product more quickly.

The bone sample undergoes a decalcification process by mixing it with hydrochloric acid. This process separates the gelatinous bone protein from the rest of the sample, which is then filtered to remove any contaminants and obtain a reliable measurement. Although the chemicals used in the pretreatment process may vary depending on the sample, the purpose is always to isolate the necessary components for accurate dating results.27

Preparation of a sample specifically tailored to liquid scintillation will now be described. After the pretreatment process, the resulting material is freeze-dried to eliminate any excess water, which often leads to the creation of a white powder-like substance. The sample is then placed inside a combustion tube along with an inert medium of quartz silica and combusted to produce carbon dioxide according to:28

C₆H₈O₂N₁ (s) + 6O₂ (g) → 6CO₂ (g) + 4H₂O (g) + N₂ (g)

This is followed by a step where carbon dioxide combines with a reactive group one metal (lithium), resulting in the formation of lithium carbide. While this happens in a series of steps, for simplicity, we can consider this as the overall reaction. The formation of lithium carbide is crucial in the production of our final organic compound:

2Li(s) + 2CO₂(g) → Li₂C₂(s) + 2CO(g)

Finally, the lithium carbide is mixed with excess water to produce lithium hydroxide and acetylene gas.

Li₂C₂(s) + 2H₂O(l) → C₂H₂(g) + 2LiOH(aq)

After the final chemical reaction, acetylene gas is passed through a column containing vanadium pentoxide, which acts as a catalyst. This particular catalyst promotes trimerisation, a process where three molecules of acetylene gas react to form benzene:29

3C₂H₂(g) → C₆H₆(l)

Benzene is mixed with a scintillator medium and placed in vials within the apparatus. The compound's decay reacts with the medium and produces flashes of light. The spectrometer counts these flashes for over a week. The resulting data is then compared to a calibration curve, which helps determine the absolute age of the sample.

Calibration curves in carbon-14 dating

Calibration curves are graphs that show the amount of carbon-14 present in a sample plotted against the known age of that sample. Knowing the amount of carbon-14 isotopes remaining in a body doesn't directly tell us the specimen's age, except in cases where only half the original amount of carbon is present, which lets us assume that the sample is 5,700 years old.30

A process called calibration is necessary to create a reliable correlation between the amount of carbon-14 present and the sample's age. This involves measuring the remaining carbon-14 in multiple specimens of known ages and creating a curve that can be used to compare other samples of the same type. To ensure accuracy, multiple calibrations using different kinds of specimens are essential.31

Conclusions

What does carbon dating tell us? The little atoms of carbon we leave behind, believe it or not, tell a story. They assign us a place in history and, coupled with other archaeological techniques, give us unique identities as to who we were in our place of time, and the history of which tells us stories of those who came before us. We better understand how their respective roles in that period have shaped the traditions we honour and follow, for the past is what shapes the future.32

Carbon dating has played a significant role in discovering and understanding the history and development of empires and periods that existed before our time. For example, in Japan, carbon dating of artefacts from the Jomon Period helped scientists determine the length of Japan's Neolithic era, giving them a glimpse into a millennium's worth of human development.33 But why does it matter? Towards the end of the Jomon Period, Japan began transitioning to the Yayoi Culture, which marked the emergence of more pronounced regional differences. This is still evident in modern-day Japan, where notable similarities exist between the Kanto and Kansai regions despite significant differences in dialect, customs and traditions.34 Carbon dating has allowed each region to honour and preserve its unique practices and explain their cultural significance.

Carbon dating has been instrumental in uncovering more information about the Indus Valley Civilisation, which was one of the largest urban civilisations of its time. Through carbon dating, it was discovered that this civilisation was actually 2,000 years older than previously estimated, placing it in the 2nd millennium BC.34 In addition, carbon dating has revealed that the Indus Valley Civilisation was the first known civilisation to create standardised weights and measures, and was actively involved in trade throughout modern-day Kuwait, Iraq, Iran and Syria - regions where its cultural influence can still be seen today.35

Carbon dating has also been actively utilised in Wairau Bar, which is considered the most significant location of the initial Māori settlement and the richest archaeological site in New Zealand. The origins of this site date back to around 1300 CE36 and it is believed to be the resting place of the Māori ancestors.37 "Various types of analyses strongly argue that the food remains are from a single event, not an accumulation over time. So simply the size of these features and the scale of the food remains leads us to think that these were communal activities, and whenever there are large-scale communal activities involving food preparation in Polynesian communities, you usually have some sort of ceremonial activity," said University of Otago, archaeologist Richard Walter in an interview with RNZ.38 Wairau Bar tells us a story of the origins of our ancestors, where they came from and why we honour our cultural practices all of which are made possible due to carbon dating.

References

- American Chemical Society National Historic Chemical Landmarks. Discovery of Radiocarbon Dating [Online]; ACS, 2016. http://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/radiocarbon-dating.html (accessed 11/03/2024).

- Beta Analytic. What is Carbon-14 (14C) Dating? Carbon Dating Definition [Online]; SGS, n.d. https://www.radiocarbon.com/about-carbon-dating.htm (accessed 11/03/2024).

- Brain, M.; Bowie, D. How Nuclear Radiation Works. HowStuffWorks, September 7, 2023. https://science.howstuffworks.com/nuclear-radiation.htm (accessed 11/03/2024).

- M. Vidale et al. Expedition Magazine, Sept. 2016, 58 (2).

- South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology. Ötzi the Iceman [Online]. https://www.iceman.it/en/ (accessed 11/03/2024).

- Ministère de la Culture. Dating the figures at Lascaux [Online]. https://archeologie.culture.gouv.fr/lascaux/en (accessed 11/03/2024).

- Tedesco, L.A. Lascaux (ca. 15,000 B.C.) Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Oct. 2000. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/lasc/hd_lasc.htm (accessed 15/3/2024).

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Ocean Facts: The Carbon Cycle [Online]; NOAA, n.d. https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/carbon-cycle.html#transcript (accessed 02/04/2024).

- Jones, M.; Fosbery, R.; Taylor, D.; Gregory, J. Cambridge International AS & A Level Biology Coursebook with Digital Access (2 Years), 5th ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2020.

- National Geographic Education. Food Chain [Online]; NAT GEO, n.d. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/food-chain/ (accessed 02/04/2024).

- Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Carbon-14. In Encyclopedia Britannica; April 9, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/science/carbon-14 (accessed 02/04/2024).

- Khadilkar, D. How carbon-14 discovery transformed science. RFI, March 14, 2020. https://www.rfi.fr/en/science-and-technology/20200314-how-carbon-14-discovery-transformed-science (accessed 02/04/2024).

- Helmenstine, A. M. Why Radioactive Decay Occurs. ThoughtCo, 2019, December 4. https://www.thoughtco.com/why-radioactive-decay-occurs-608649 (accessed 02/04/2024).

- LibreTexts. Half-Life. In Introductory Chemistry: Basics of General Organic and Biological Chemistry; Ball, D.W., Hill, R.H., & Scott, J.S. (Eds.); LibreTexts, n.d. https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_Chemistry/Basics_of_General_Organic_and_Biological_Chemistry_(Ball_et_al.)/11%3A_Nuclear_Chemistry/11.02%3A_Half-Life (accessed 02/04/2024).

- Kutschera, W. Radiocarbon 2019, 61(5), 1135-1142. DOI: 10.1017/RDC.2019.26

- Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Beta Decay. In Encyclopedia Britannica; March 15, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/science/beta-decay (accessed 03/04/2024).

- Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency. Beta Particles. https://www.arpansa.gov.au/understanding-radiation/what-is-radiation/ionising-radiation/beta-particles (accessed 03/04/2024).

- The University of Waikato. C-14 Carbon Dating Process. Science Learning Hub, September 17, 2009. https://www.sciencelearn.org.nz/image_maps/37-c-14-carbon-dating-process (accessed 03/04/2024).

- L'Angelis, M. F., Ed. Handbook of Radioactivity Analysis; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, 2003.

- University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Liquid Scintillation Counting. 2016. https://uwm.edu/safety-health/wp-content/uploads/sites/405/2016/11/HANDOUT.pdf (accessed 05/04/2024).

- Knoll, G. F. Radiation Detection and Measurement, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ, 2010.

- Elsborg, L. Gas Proportional Counting Compared with Liquid Scintillation Counting for Assaying Tritium in Biological Materials. J. Nucl. Med. 2001, 15 (2), 115. https://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/jnumed/15/2/115.full.pdf.

- Nnane, I. P.; Tao, X. Drug Metabolism | Isotope Studies. In: Encyclopedia of Analytical Science 2nd ed .; P. Worsfold, A. Townshend, & C. Poole., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2005.

- Teuscher, N. Understanding Accelerator Mass Spectrometry. Certara Knowledge Base, September 23, 2013. https://www.certara.com/knowledge-base/understanding-accelerator-mass-spectrometry/ (accessed 05/04/2024).

- Walther, C.; Wendt, K. Radioisotope Mass Spectrometry. In: Handbook of Radioactivity Analysis, 4th ed., L'Annunziata, M. F., Smith, K. L., Eds.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, 2020.

- University of Waikato. Operating Procedures for Radiocarbon Dating Pretreatment. https://www.waikato.ac.nz/research/research-services-facilities/radiocarbon-dating/operating-procedures/pretreatment (accessed 06/04/2024).

- The University of Waikato. C-14 carbon dating process. Science Learning Hub, September 17, 2009. https://www.sciencelearn.org.nz/image_maps/37-c-14-carbon-dating-process (accessed 06/04/2024).

- Nozaki, K.; Shimada, T. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15 (42), 8326-8333. DOI: 10.1039/C7OB01885A.

- Science Learning Hub. Radiocarbon calibration curves. February 2, 2023. https://www.sciencelearn.org.nz/resources/3203-radiocarbon-calibration-curves (accessed 07/04/2024).

- Hua, Q. Radiocarbon Dating. Science Education Resource Center, Carleton College. https://serc.carleton.edu/vignettes/collection/35379.html (accessed 07/04/2024).

- MOOC. Why Is It Important to Study History? MOOC.org Blog, December 16, 2021. https://www.mooc.org/blog/why-is-it-important-to-study-history (accessed 07/04/2024).

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Japanese Momoyama Period (1573–1615). October 2002. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/jomo/hd_jomo.htm (accessed 09/04/2024).

- Web Japan. Regions of Japan. https://web-japan.org/kidsweb/explore/regions/index.html (accessed 10/04/2024).

- Lumen Learning. Harappan Culture. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-hccc-worldcivilization/chapter/harappan-culture/ (accessed 10/04/2024).

- McKinnon, M. Marlborough Region - Early Māori History. In Te Ara - The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/photograph/31750/wairau-bar-ancient-rubbish-dump (accessed 11/04/2024).

- Marlborough Museum. Wairau Bar. https://www.marlboroughmuseum.org.nz/exhibitions/wairau-bar (accessed 11/04/2024).

- Radio New Zealand. Wairau Bar: How It All Began. Our Changing World. https://www.rnz.co.nz/national/programmes/ourchangingworld/audio/201807075/wairau-bar-how-it-all-began (accessed 12/04/2024).

- University of Otago. History Unearthed. https://www.otago.ac.nz/profiles/historyunearthed (accessed 12/04/2024).